SAN FRANCISCO ART INSTITUTE

Through Ken Conner I’d met La Cienega gallerist Rex Evans, who carried big-name, blue chip art. Ken and his parents, collectors, had bought work from Evans. Ken encouraged me to show him my work and he put me on the gallery roster, featured in a few group shows. It was a big deal for me at age seventeen. The previous summer, Ken had taken classes at the La Jolla Museum of Art school, about thirty miles from where he lived on an avocado ranch owned by his parents. He suggested I could live with him on the ranch, help out, and commute to school. I was still living at home with mom, but was restless. I was excited at the possibility of taking classes from John Altoon, who had taught at the La Jolla Museum art school the past summer. He was one of the art heroes whose work I had been seeing in Los Angeles galleries. I applied to the school and was accepted. I moved down to San Marcos with Ken and would go home to Corona del Mar on weekends to do my laundry and hang out. My mother gave me her old pink and gray ’52 Chevy two-door and I would commute down to La Jolla for my two classes a week. I discovered José Luis Cuevas, a prodigy from Mexico City, who had been showing his work since his teen years. I got into Cuevas in a big way, and his gallerist, Silvan Simone, told us Cuevas was in L.A., making lithographs at Tamarind Press and said we should visit him. We went over to the little bungalow where they’d set him up, and awkwardly tried to express how much we admired his work. Only thing, he spoke virtually no English and Ken only knew a smattering of Spanish.

Unfortunately, Altoon did not teach that summer, but I finished the semester at La Jolla. Since I was about to turn eighteen and become eligible for the draft, I needed to enroll in an accredited school for a draft deferment. I moved back to my mother’s house and entered Orange Coast Junior College in January 1963.

At Orange Coast, I hooked up with a terrific teacher, Bruce Piner, a younger teacher in his thirties with great art history savvy and an appreciation of current movements. I liked Pop Art okay and sensed how important it was— a knockout first show of Lichtenstein’s at Ferus Gallery had a huge impact. I did a series of three Pop paintings of tattoos, pink arms on flat, colored backgrounds. They all had tattoos about “Mom.” There was a famous old-time tattoo of a garland of flowers, with the slogan “The sweetest girl I ever kissed was another man’s wife. My mother.” It probably originally came from an embroidered pillow, something for sailors. I called it “Mom Art.”

I was hanging out a lot with Richard Shaw and still saw Doug Hall, who was attending Long Beach State and started etching. He became a printmaking major, the first person I knew to get into etching. I signed up for printmaking at Orange Coast.

Piner was eager to have all of us explore things, but he wasn’t making his own art. We all thought we would go through graduate school and get a job teaching art, but we hoped we wouldn’t wind up like that, not having made any new work in years. I was reading a wide range of art history, musing over a biography of Toulouse Lautrec and all the other artists who were in the mix with him, wondering if our crew was going be like that. None of us had any idea what we were doing. We had no agendas. But we were on fire to make the work and carve out a place in the world that wasn’t what was expected of us.

In Piner’s art history class, I sat next to David Mackenzie, a talented young artist from Huntington Beach. He and I were very taken with surrealism and Dada-esque pranks, fancied ourselves as apple cart upsetters. When Piner showed the darkened auditorium the slide of Meret Oppenheim’s fur-lined teacup, a famous surrealist piece, McKenzie blew a huge whoop through a super-loud plastic whistle and disrupted the class. Like the Dadas did. Like the Impressionists, Picasso.

“None of us had any idea what we were doing. We had no agendas. But we were on fire to make the work and carve out a place in the world that wasn’t what was expected of us.“

My hometown area was so right wing, birthplace of the John Birch Society and all that, that when Mackenzie pulled a stunt in the school courtyard where he came to school wrapped in an American flag, he came close to getting thrown out of school for desecrating the flag. It was a great pressure cooker, though, because it made us really want to get out of there. I went through two semesters at Coast. I learned to etch a little bit. I made a bunch of art.

Mackenzie and I took a weekend run to San Francisco. I had not been on an airplane since I was an infant. Our friends who were going to the Art Institute picked us up in their VW bug and drove straight to North Beach, where they were all living near the school. We quickly made our way to Grant Avenue, Dean Moriarty’s neighborhood from On the Road and ground zero for the beatnik coffee houses and jazz joints on a Friday night. I couldn’t believe I was still in California: the Victorian architecture, weird stores, ethnic restaurants. There was a gay club holding a drag queen contest and these limos kept pulling up and the queens would climb out and walk into the club. California? I could have been on Mars. I was smitten.

I applied to the San Francisco Art Institute and was accepted for the fall 1963 semester. My mother helped with the $385-per-semester tuition. I didn’t work all the time I went to Orange Coast, just skated, living at home, selling a piece here and there. At the Art Institute, I took a job on the maintenance crew, swabbing out the bathrooms and sweeping up the cafeteria. Dave Getz worked on the same crew, but he hadn’t yet started playing drums in Big Brother and the Holding Company—the SF music scene, hippies, and LSD were all looming on the horizon. David Mackenzie was also accepted and he and I moved up with another art student we knew from Orange Coast College. We rented a duplex between Columbus Avenue and Taylor Street in the heart of North Beach. It was my first apartment and the rent was seventy-five bucks a month.

The Art Institute was located in an ivy-covered building from the twenties. They had a big Diego Rivera mural, which, in those days, was covered over. Only about four hundred students attended and classes were small. Rothko and a lot of great New York painters had taught there, as well as the seminal Bay area painters that turned things around in the late 1950s. But San Francisco was a long way from New York and, although I loved a lot of the ab-ex painters, de Kooning and Kline and those guys, as well as the great cultural energy that emanated from New York, we were hyper-aware that it was a different thing in San Francisco. Bay Area figurative painting was a big breakthrough from the tyranny of abstract expressionism. Richard Diebenkorn, Joan Brown, Elmer Bischoff, and other Bay Area painters segued out of the muscular slash-and-burn abstract expressionist stuff and began going back to recognizable subject matter.

These were important distinctions, almost philosophical concerns or belief systems. Abstract art was supposed to be a search for purity of expression and it was not cool to do recognizable subject matter (although de Kooning always floated in and out of that). But these Bay Area people were fantastic painters who decided to turn back to landscapes and figures, but with loose paint, very expressive. It wasn’t tight, representational work, but beautiful, killer painting. The Art Institute may have been a long way from the Park Avenue galleries, but it was a hive of intellectual activity and creative expression.

There were people on the faculty such as Richard Miller, who was a total raging, political subversive, and would give firebrand talks to his classes, and Ken Lash, a poet who lived in Bolinas. We read Joseph Campbell’s Hero With A Thousand Faces in one class, introducing me to the common threads connecting all primary philosophies and belief systems. I was getting a glimpse of a wider world.

I took a drawing class from Joan Brown, whose powerful work transfixed me when I’d first seen it in Los Angeles galleries. She was married to Manuel Neri, who led a sculpture class I took. She was another one of the reasons I wanted to come to San Francisco. Her work was super-gutsy; thick paint, great, crazy brushwork, and everyday themes. She grew up in San Francisco, attending Catholic schools, when she saw an advertisement for the Art Institute in a bus and decided to pursue art. She was something of a prodigy and was enrolled in the Art Institute while she was a teenager. She studied with Diebenkorn and Bischoff, among others. She was really cute and also full of piss and vinegar. Swore like a trooper and could drink anybody under the table, Joan was like everybody’s sweetheart. We were all in love with her.

When I got to the Art Institute, Shaw had been there already for two semesters and was deeply involved in ceramics. He was painting also, but ceramics became his thing, largely through his work with Ron Nagle, the madman of clay, who scared all of us a little and was a protégé of Peter Voulkos. I came to San Francisco wanting to be a lithographer. I was in love with lithographs, all the dark tones and the washes that you get working on the stones. They had ancient Bavarian limestones at the Art Institute, the traditional printing medium for lithography since its beginning in the 18th century. These came, along with the big old presses, from when the school started in the late 1800s. They were supposedly used for ballast on the sailing ships that brought Gold Rush miners to the city.

I loved mediums that had specific craft parameters, stringent demands involving tools and techniques that had to be done a certain way. Whether it was ceramics, printmaking, tattooing or pinstriping, if you couldn’t handle the utensils, you couldn’t get it right. I dug the history of printmaking and the eccentricity of a lot of printmakers. Even if they were primarily painters, it brought out a certain thing in artists that I really responded to. I liked monochromatic art in black and white and gray tones. I loved the dark shades you could get with lithos, and I liked the idea that it was a multiple original. I liked the democratic, anti-elitist nature of a populist medium.

I took a lithography class from the head of the print department, Dick Graf, and also signed up for an etching class. The big city swagger of the other students intimidated me. One character actually wore a beret at a jaunty angle, about the corniest thing in the world, but he did it with such arrogance and authority, I couldn’t help but be impressed. I had been worried about how I was going to fit in with these people, how I could compete, feeling threatened and insecure. I knew how green I was. But then I looked around at the art they were making – especially the guy in the beret – and realized they weren’t that advanced, after all. “These people don’t know what they’re doing,” I thought. “I can draw rings around them.”

“These people don’t know what they’re doing,” I thought. “I can draw rings around them.”

I started doing lithography. I liked the challenge of working with the medium , but wasn’t loving it. Graf kept asking what the deeper meanings of my work were, what I was trying to convey. I had no idea, no big intellectual program to articulate, and he didn’t think much of that. The etching class met two nights a week and on Saturdays with Gordon Cook, who was unlike anybody I ever met before. He was a tough, blue-collar guy from Chicago who distrusted academia and kept his day job as a typesetter in the printing trade, and only taught on the side. He was a big guy, dour and contrary, kind of scary, but he did incredibly nuanced, delicate etchings of still lifes, nudes and landscapes, all drawn from life, minimal means, super masterly. The first time I met Cook was before I was enrolled, when I was up on a visit with Richard and Martha, who were taking printmaking. I sat in with them and they told me to work on a plate. I etched kind of a fantasy thing of my buddy Mackenzie as kind of a heroic figure with the eagle wings that I learned to draw when I was obsessed with tattooing. Cook came over and looked at what I was doing.

“That’s not very straightforward,” he said.

“Maybe I’m not a very straightforward guy,” I said. It just popped out. I didn’t think about what I was saying. We instantly hit it off.

He talked about art in a way I had never heard before – super-intelligent, no bullshit, from his blue-collar perspective, which I could understand, talking about it in a way that combined a complete embrace of colloquial things in life, down to the metaphors he used, with his deep grounding in art history, tying in Rembrandt and Durer and this great printmaking tradition. He saw my potential. He kept coming up with stuff that was really hard to do, challenging me. “Why don’t you do this?” He showed me the value of looking at nature, very hard, and figuring out a way to translate it into something that would convey your feelings in the picture. You’re creating a picture with very fine lines and matrixes of lines, networks of things, stipples, making marks to create an illusion of something, whether it’s a can full of dried flowers or a landscape of a San Francisco back yard with a million leaves and bushes. Essentially it was about perceiving the greater network of the world through hallucinatory attention to details, instead of imposing an attitude or agenda with the work. The goal was to transmit emotions that cannot be rendered into words. Cook kicked a door open for me that nobody else had. He became my mentor. Gordon was well versed in Asian aesthetics. He was a journeyman union typesetter, and only taught classes at night and on the weekends. His day job was setting hand type, and he was proud of the tradition of book-making.

One day, he showed me something from a magazine by two American expatriates living in Kyoto, artist Will Peterson and the beat poet Cid Corman — an English translation of a text about how to act by Zeami, the fourteenth century Japanese inventor of Noh drama. Basically, it was a Taoist way of looking at the universe in a nutshell, instructions on how to behave in life and make it work, specifically related to the medium that you happen to be working in. For them, it was theater. Zeami related everything to nature; like a flower, you open up, and all the parts come together. I was stunned. Cook asked me what I thought it was about.

“It’s about acting,” I said.

“It’s about everything,” Cook said. I copied it down and still keep it.

We all started hanging out together, going for drinks at the San Remo, a couple of blocks down the hill from school. I was on a social footing with my teachers. I was working hard, making prints and drawing, even painting a little bit. I desperately wanted to be a painter, but I did not know what to paint. I loved the physicality of oil paint, but I was always completely lost with what I should do with it. I didn’t have an original thought in my head about that. I didn’t have an original thought about printmaking, either. I tended to imitate somebody that I admired. I’d done that all the way through. When I got into Goya, I did a self-portrait a la Goya. I wanted to be like these people. I wanted to mind-meld with them by looking at their work and imitating it. I did it with Cuevas.

The answers seemed to be floating in the San Francisco air and all you had to do was breathe them in. Once I was in school, I was filled with anticipation. They’re going to give us the keys to the kingdom. They’re going to draw back the curtain, and give up the secrets of how to do art. They maintained a great tradition—which may have originally come from the abstract expressionists—of not being explicitly verbal, avoiding intellectual flights of clap-trap, and not sitting around pontificating about cosmic essences.

Very quickly during the first semester, I became frustrated and impatient. I had taken a few sessions of my sculpture class with Neri and I went over to Shaw. “Neri won’t really say anything,” I said.

“That’s the way it is,” he said. We had to absorb mastery by observation, figure it out for ourselves.

I didn’t have any money. I’d go to City Lights Books and sit in the basement and read whole books. I spent many nights down there. I was drinking it all up. I lived in that apartment for a couple of semesters, making serious etchings. Martha and I were kind of the leading lights of the printmaking students and Gordon was giving us very hard things to do. He told us to do an etching of the City of San Francisco. We went to Twin Peaks and each of us did a 24 x 30” copper plate, drawing the exacting details of a vast panorama wirh åa needle through beeswax. We sat there, trying to concentrate, holding down the heavy plates in the wind, and fending off comments by tourists alighting from the tour buses. It was great training.

Adapted from Wear Your Dreams – My Life in Tattoos by Ed Hardy, St. Martin’s Press, 2013

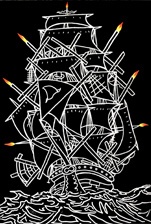

NEW PRINT

A Burial at Sea,

28"h. x 22"w.

Color lithograph, Edition of 20

View at Shark's Ink

© Don Ed Hardy – All Rights Reserved – Privacy Policy